In the year 1994,

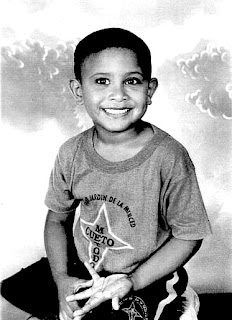

Rolandito Salas Jusino was born. I was four that year. He was four

when he disappeared.

In other words he was by

himself in the community park and he was four and he had mousy ears and he was

four and he was light-skinned and he was four and he smiled through many milk

carton photographs and he smiled frozenly, smiled frozenly four, in many news

reports and in many news hours and news half hours and news quarterly reports

and commentary sessions and black and white El Nuevo Día Puerto Rico’s Finest

Newspaper shots and in many Front Page color shots—smiling frozenly four: a

smile that’s fit to print, frozen into the year 1999, his eyes emanating from

some center, his eyes in print and in monitor seeing the eyes seeing him on the

milk cartons and the reports and the television screens and the FBI Missing

Persons page.

He was called Rolandito

like I was called by my parents and my grandparents. But this is about

Rolandito not about me, this is about a four year old, actually no it’s about

something else, it’s not about 1999 when he was 4 and I was 8, it’s about 2000

when I was a little older, a little young but still a little older, and

Rolandito was still four even though he might have been older too, because he

was frozen.

I

was nine maybe and I was in a classroom with drawings of test tubes on the

walls and it was always hot in there we were talking, I think maybe we had gone

off-topic and the off-topic topic was done with and we were just talking about

something off the off-topic, and I don’t know how it was brought up,

conversation-wise, but I know that it all started with a raised hand, the

raised hand of a boy, a boy named Christian, or that’s how it starts for me in

my memory anyway, with the teacher looking at a seat behind me, me turning my

head to see the raised hand of Christian, the athletic boy who never let me

play volleyball, who always had an it-wasn’t-me

face.

He said, “Missi,” as in

Missus, pronounced Mee-See—he said “Missi,” as in Teacher, as in Maybe You Have

The Answer Because I Didn’t Ask My Mom Because I Don’t Ask My Mom Things Like

This—he said with his hand up, “Missi,” and Missi said, “Yes?” “Missi, I was in

the supermercado the other day, I was with my mom, and we were at the cashier’s

box, paying, I mean I wasn’t paying but my mom was,” and the lighting was

fluorescent and pale and people always look gray then, “and two aisles ahead, I

saw Rolandito’s mom.”

Rolandito’s mom, unlike

Rolandito, was not frozen, and the year 1999 ended and 2000 began and time

continued for her and the only way Rolandito grew for her was through those

digitized age progression pictures. Or that frozen one.

“I saw Rolandito’s mom,”

Christian said, “and I didn’t get it, Missi.” And then Missi said, “What didn’t

you get, Christian?” And Christian said, “Well, it’s just,” and he even rolled

his eyes a little bit, because he knew it was very obvious, “it’s just that she

wasn’t crying.”

And so Missi, middle-aged

and attractive, Missi who had her own daughters and her volleyball body and her

volleyball career and her volleyball hotness and who taught science and who had

a great ass even though I didn’t know about great asses then or if I did I

wasn’t aware on the “Look She Has A Great Ass” level—Missi with the great ass

said, “Well, Christian, life goes on.”

Now we were all confused:

how can life go on? She expanded: “We can’t always be crying in the

supermercados and the supermalls and the supermax and the wal mart,” she said

or something like that, “we need to do what we need to do. Believe me,

Rolandito’s mom had had a lot of time to cry. And maybe she still does, but not

in the supermercados. It’s okay not to cry at the supermercados.” But Christian

still didn’t understand, I could tell.

I didn’t understand it either.

I didn’t understand it either.

No comments:

Post a Comment